History of Ismailis: From The Ubaydi(Fatimid) Empire To Modern Day Agha Khan

------------------------------------------------------------------------

A major branch of the Shi'ah, the Ismailiyyah traces the line of imams through Ismail, son of Imam Jafar Al-Sadiq (d. AH 148/765 CE). Ismail was initially designated by Jafar as his successor but predeceased him. Some of Jafar’s followers who considered the designation irreversible either denied the death of Ismail or accepted Ismail’s son Muhammad as the rightful imam after Jafar.

Some People Associated with Ismailis(Agha Khanis):

The Fatimid Ubaydi Kaffir Empire

(909AD-1171AD)

Agha Khan and his Familiy

Muhammad Shah Agha Khan

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

THE PRE-FATIMID AGE.

The communal and doctrinal history of the Ismailiyah in this period poses major problems that are still unresolved for lack of reliable sources. The Muslim heresiographers mostly speak of two Ismaili groups after the death of Imam Jafar: The “pure Ismailiyyah” held that Ismail had not died and would return as the Qaim (mahdi), while the Mubarakiyah recognized Muhammad ibn Ismail as their imam. According to the heresiographers, Al-Mubarak was the name of their chief, a freedman of Ismail. It seems, however, that the name (meaning “the blessed”), was applied to Ismail by his followers, and thus the name Mubarakiyah must at first have referred to them. After the death of Jafar most of them evidently accepted Muhammad ibn Ismail as their imam in the absence of Ismail. Twelver Shiia reports attribute a major role among the early backers of Ismail to the Khattabiyah, the followers of the extremist Shiia heresiarch Abu Al-Khattab (d. 755?). Whatever the reliability of such reports, later Ismaili teaching generally shows few traces of Khattabi doctrine and repudiates Abu Al-Khattab. An eccentric work reflecting a Khattabi tradition, the Umm Al-kitab (Mother of the book) transmitted by the Ismailiyyah of Badakhshan, is clearly a late adaptation of non-Ismaili material.

Nothing is known about the fate of these Ismaili splinter sects arising in Kufa in Iraq on the death of Imam Jafar, and it can be surmised that they were numerically insignificant. But about a hundred years later, after the middle of the third century AH (ninth century CE), the Ismailiyyah reappeared in history, now as a well-organized, secret revolutionary movement with an elaborate doctrinal system spread by missionaries called daees (“summoners”) throughout much of the Islamic world. The movement was centrally directed, at first apparently from Ahwaz in southwestern Iran. Recognizing Muhammad ibn Ismail as its imam, it held that he had disappeared and would return in the near future as the Qaim to fill the world with justice.

Early doctrines. The religious doctrine of this period, which is largely reconstructed from later Ismaili sources and anti-Ismaili accounts, distinguished between the outer, exoteric (zahir) and the inner, esoteric (batin) aspects of religion. Because of this belief in a batin aspect, fundamental also to most later Ismaili thought, the Ismailiyyah were often called batiniyah, a name that sometimes has a wider application, however. The zahir aspect consists of the apparent, directly accessible meaning of the scriptures brought by the prophets and the religious laws contained in them; it differs in each scripture. The batin consists of the esoteric, unchangeable truths (haqaiq) hidden in all scriptures and laws behind the apparent sense and revealed by the method of esoteric interpretation called ta'wil, which often relied on qabbalistic manipulation of the mystical significance of letters and their numerical equivalents. The esoteric truths embody a gnostic cosmology and a cyclical, yet teleological history of revelation.

The supreme God is the Absolute One, who is beyond cognizance. Through his intention (iradah) and will (mashi'ah) he created a light which he addressed with the Qur'anic creative imperative, kun (“Be!”), consisting of the letters kaf and noon. Through duplication, the first, preceding (sabiq) principle, Kuni (“be,” fem.) proceeded from them and in turn was ordered by God to create the second, following (tali) principle, Qadar (“measure, decree”). Kuni represented the female principle and Qadar, the male; together they were comprised of seven letters (the short vowels of Qadar are not considered letters in Arabic), which were called the seven higher letters (huruf ulwiyah) and were interpreted as the archetypes of the seven messenger prophets and their scriptures. In the spiritual world, Kuni created seven cherubs (karubiyah) and Qadar, on Kuni’s order, twelve spiritual ranks (hudud ruhaniyah). Another six ranks emanated from Kuni when she initially failed to recognize the existence of the creator above her. The fact that these six originated without her will through the power of the creator then moved her to recognize him with the testimony that “There is no god but God,” and to deny her own divinity. Three of these ranks were above her and three below; among the latter was Iblis, who refused Kuni’s order to submit to Qadar, the heavenly Adam, and thus became the chief devil. Kuni and Qadar also formed a pentad together with three spiritual forces, Jadd, Fath , and Khayal, which were often identified with the archangels Jibra'il, Mikha'il, and Israfil and mediated between the spiritual world and the religious hierarchy in the physical world.

The lower, physical world was created through the mediation of Kuni and Qadar, with the ranks of the religious teaching hierarchy corresponding closely to the ranks of the higher, spiritual world. The history of revelation proceeded through seven prophetic eras or cycles, each inaugurated by a speaker (natiq) prophet bringing a fresh divine message. The first six speaker-prophets, Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, Jesus, and Muhammad, were each succeeded by a legatee (wasi) or silent one (samit) who revealed the esoteric meaning hidden in their messages. Each legatee was succeeded by seven imams, the last of whom would rise in rank to become the speaker of the next cycle and bring a new scripture and law abrogating the previous one. In the era of Muhammad, Ali was the legatee and Muhammad ibn Ismail the seventh imam. Upon his return Muhammad ibn Ismail would become the seventh speaker prophet and abrogate the law of Islam. His divine message would not entail a new law, however, but consist in the full revelation of the previously hidden esoteric truths. As the eschatological Qaim and mahdi, he would rule the world and consummate it. During his absence, the teaching hierarchy was headed by twelve hujjahs residing in the twelve provinces (jaza'ir). Below them were several ranks of daees. The number and names of these ranks given in early Ismaili texts vary widely and reflect speculative concerns rather than the actual organization of the hierarchy, about which little is known for either the pre-Fatimid or Fatimid age. Before the advent of the Qaim, the teaching of the esoteric truths must be kept secret. The neophyte had to swear an oath of initiation vowing strict secrecy and to pay a fee. Initiation was clearly gradual, but there is no evidence of a number of strictly defined grades; the accounts of anti-Ismaili sources that name and describe seven or nine such grades leading to the final stage of pure atheism and libertinism deserve no credit.

Emergence of the movement. The sudden appearance of a widespread, centrally organized Ismaili movement with an elaborate doctrine after the middle of the ninth century suggests that its founder was active at that time. The Muslim anti-Ismaili polemicists of the following century name as this founder one Abd Allah ibn Maymun Al-Qaddah . They describe his father, Maymun Al-Qaddah , as a Bardesanian(Gnostic Follower) who became a follower of Abu Al-Khattab and founded an extremist sect called the Maymuniyah. According to this account, Abd Allah conspired to subvert Islam from the inside by pretending to be a Shiia working on behalf of Muhammad ibn Ismail. He founded the movement in the latter’s name with its seven grades of initiation leading to atheism and sent his daees abroad. At first he was active near Ahwaz and later moved to Basra and to Salamiyah in Syria; the later leaders of the movement and the Fatimid caliphs were his descendants. This story is obviously anachronistic in placing Abd Allah’s activity over a century later than that of his father. Moreover, Twelver Shiia sources mention Maymun Al-Qaddah and his son Abd Allah as faithful companions of Imams Muhammad Al-Baqir (d. 735?) and Jafar Al-Sadiq respectively. They do not suggest that either of them was inclined to extremism. It is thus unlikely that Abd Allah ibn Maymun played any role in the original Ismaili sect and impossible that he is the founder of the ninth-century movement. The Muslim polemicists’ story about Abd Allah ibn Maymun is, however, based on Ismaili sources. At least some early Ismaili communities believed that the leaders of the movement including the first Fatimid caliph, Al-mahdi, were not Alids but descendants of Maymun Al-Qaddah . The Fatimids tried to counter such beliefs by maintaining that their Alid ancestors had used names such as Al-Mubarak, Maymun, and Sa'id in order to hide their identity. While such a use of cover names is not implausible, it does not explain how Maymun, allegedly the cover name of Muhammad ibn Ismail, could have become identified with Maymun Al-Qaddah . It has, on the other hand, been suggested that some descendants of Abd Allah ibn Maymun may have played a leading part in the ninth-century movement. The matter evidently cannot be resolved at present. It is certain, however, that the leaders of the movement, the ancestors of the Fatimids, claimed neither descent from Muhammad ibn Ismail nor the status of imams, even among their closest daees, but described themselves as hujjahs of the absent imam Muhammad ibn Ismail.

The esoteric doctrine of the movement was of a distinctly gnostic nature. Many structural elements, themes, and concepts have parallels in various earlier gnostic systems, although no specific sources or models can be discerned. Rather, the basic system gives the impression of an entirely fresh, essentially Shiia adaptation of various widespread gnostic motives. Clearly without foundation are the assertions of the anti-Ismaili polemicists and heresiographers that the Ismailiyyah was derived from various dualist religions, such as Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism, Bardesanism, Mazdakism, and the Khurramdiniyah.

The movement was rent by a schism about 899 after Abd Allah (Ubayd Allah), the future Fatimid caliph Al-mahdi, succeeded to the leadership. Repudiating the belief in the imamate of Muhammad ibn Ismail and his return as the mahdi, Al-mahdi claimed the imamate for himself. He explained to the daees that his predecessors in the leadership had been legitimate imams but had concealed their rank and identity out of caution. They were descendants of Imam Jafar’s son Abd Allah, who had been the rightful successor to the imamate rather than Ismail; the names of Ismail and his son Muhammad had merely been used to cover up their identity as the imams.

This apparently radical change of doctrine was not accepted by some of the leading daees. In the region of Kufa, hamdan Qarmat and Abdan broke with Al-mahdi and discontinued their missionary activity. Qarmat ’s followers were called the Qaramitah, and the name was often extended to other communities that broke with the Fatimid leadership, and sometimes to the Ismailiyyah in general; it will be used here for those Ismailiyyah who did not recognize the Fatimid imamate. Abdan was the first author of the movement’s books. He was murdered by a daee initially loyal to Al-mahdi, and hamdan Qarmat disappeared. On the west coast of the Arabian Gulf, the daee Abu Sa'id Al-Jannabi followed the lead of Qarmat and Abdan, who had invested him with his mission. He had already seized a number of towns, including Al-Qatif and Al-Ahsa, and had thus laid the foundation of the Qarmati state of Bahrain. Other communities that repudiated Al-mahdi’s claim to the imamate were in the region of Rayy in northwestern Iran, in Khorasan, and in Transoxiana. Most prominent among the daees who remained loyal to Al-mahdi was Ibn hawshab, known as Mansur Al-Yaman, the senior missionary in the Yemen. He had brought the region of Jabal Maswar under his control, while his younger colleague and rival, Ali ibn Al-Fadl, was active in the Bilad Yafi further southwest. The daee Abu Abd Allah Al-Shii, whom Mansur Al-Yaman had sent to the Kutamah Berber tribe in the mountains of eastern Algeria, and probably also the daee Al-Haytham, whom he had dispatched to Sind, remained loyal to Al-mahdi. Some of the Ismailiyyah in Khorasan also accepted his claim to the imamate. Residing at this time in Salamiyah, Al-mahdi then left for Egypt together with his son, the later caliph Al-Qaim, as his safety was threatened because of the disaffection of the leading Syrian daee. At first he intended to proclaim himself as the mahdi in the Yemen. Increasing doubts about the loyalty of Ali ibn Al-Fadl, who later openly defected, seem to have influenced his decision to go to the Maghreb, where Abu Abd Allah Al-Shii, having overthrown the Aghlabids and seized Tunisia, proclaimed him caliph and mahdi in 910.

THE FATIMID AGE (910–1171). With the establishment of the Fatimid counter caliphate, the Ismaili challenge to Islam reached its peak and provoked a vehement political and intellectual reaction. The Ismailiyyah came to be condemned by orthodox Muslim theologians as the enemies of Islam. The Fatimid Ismailiyyah was weakened by serious splits, first that of the Qaramitah and later those of the Druzes, the Nizariyah, and the Tayyibiyah.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

A major branch of the Shi'ah, the Ismailiyyah traces the line of imams through Ismail, son of Imam Jafar Al-Sadiq (d. AH 148/765 CE). Ismail was initially designated by Jafar as his successor but predeceased him. Some of Jafar’s followers who considered the designation irreversible either denied the death of Ismail or accepted Ismail’s son Muhammad as the rightful imam after Jafar.

Some People Associated with Ismailis(Agha Khanis):

The Fatimid Ubaydi Kaffir Empire

(909AD-1171AD)

Agha Khan and his Familiy

Muhammad Shah Agha Khan

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

THE PRE-FATIMID AGE.

The communal and doctrinal history of the Ismailiyah in this period poses major problems that are still unresolved for lack of reliable sources. The Muslim heresiographers mostly speak of two Ismaili groups after the death of Imam Jafar: The “pure Ismailiyyah” held that Ismail had not died and would return as the Qaim (mahdi), while the Mubarakiyah recognized Muhammad ibn Ismail as their imam. According to the heresiographers, Al-Mubarak was the name of their chief, a freedman of Ismail. It seems, however, that the name (meaning “the blessed”), was applied to Ismail by his followers, and thus the name Mubarakiyah must at first have referred to them. After the death of Jafar most of them evidently accepted Muhammad ibn Ismail as their imam in the absence of Ismail. Twelver Shiia reports attribute a major role among the early backers of Ismail to the Khattabiyah, the followers of the extremist Shiia heresiarch Abu Al-Khattab (d. 755?). Whatever the reliability of such reports, later Ismaili teaching generally shows few traces of Khattabi doctrine and repudiates Abu Al-Khattab. An eccentric work reflecting a Khattabi tradition, the Umm Al-kitab (Mother of the book) transmitted by the Ismailiyyah of Badakhshan, is clearly a late adaptation of non-Ismaili material.

Nothing is known about the fate of these Ismaili splinter sects arising in Kufa in Iraq on the death of Imam Jafar, and it can be surmised that they were numerically insignificant. But about a hundred years later, after the middle of the third century AH (ninth century CE), the Ismailiyyah reappeared in history, now as a well-organized, secret revolutionary movement with an elaborate doctrinal system spread by missionaries called daees (“summoners”) throughout much of the Islamic world. The movement was centrally directed, at first apparently from Ahwaz in southwestern Iran. Recognizing Muhammad ibn Ismail as its imam, it held that he had disappeared and would return in the near future as the Qaim to fill the world with justice.

Early doctrines. The religious doctrine of this period, which is largely reconstructed from later Ismaili sources and anti-Ismaili accounts, distinguished between the outer, exoteric (zahir) and the inner, esoteric (batin) aspects of religion. Because of this belief in a batin aspect, fundamental also to most later Ismaili thought, the Ismailiyyah were often called batiniyah, a name that sometimes has a wider application, however. The zahir aspect consists of the apparent, directly accessible meaning of the scriptures brought by the prophets and the religious laws contained in them; it differs in each scripture. The batin consists of the esoteric, unchangeable truths (haqaiq) hidden in all scriptures and laws behind the apparent sense and revealed by the method of esoteric interpretation called ta'wil, which often relied on qabbalistic manipulation of the mystical significance of letters and their numerical equivalents. The esoteric truths embody a gnostic cosmology and a cyclical, yet teleological history of revelation.

The supreme God is the Absolute One, who is beyond cognizance. Through his intention (iradah) and will (mashi'ah) he created a light which he addressed with the Qur'anic creative imperative, kun (“Be!”), consisting of the letters kaf and noon. Through duplication, the first, preceding (sabiq) principle, Kuni (“be,” fem.) proceeded from them and in turn was ordered by God to create the second, following (tali) principle, Qadar (“measure, decree”). Kuni represented the female principle and Qadar, the male; together they were comprised of seven letters (the short vowels of Qadar are not considered letters in Arabic), which were called the seven higher letters (huruf ulwiyah) and were interpreted as the archetypes of the seven messenger prophets and their scriptures. In the spiritual world, Kuni created seven cherubs (karubiyah) and Qadar, on Kuni’s order, twelve spiritual ranks (hudud ruhaniyah). Another six ranks emanated from Kuni when she initially failed to recognize the existence of the creator above her. The fact that these six originated without her will through the power of the creator then moved her to recognize him with the testimony that “There is no god but God,” and to deny her own divinity. Three of these ranks were above her and three below; among the latter was Iblis, who refused Kuni’s order to submit to Qadar, the heavenly Adam, and thus became the chief devil. Kuni and Qadar also formed a pentad together with three spiritual forces, Jadd, Fath , and Khayal, which were often identified with the archangels Jibra'il, Mikha'il, and Israfil and mediated between the spiritual world and the religious hierarchy in the physical world.

The lower, physical world was created through the mediation of Kuni and Qadar, with the ranks of the religious teaching hierarchy corresponding closely to the ranks of the higher, spiritual world. The history of revelation proceeded through seven prophetic eras or cycles, each inaugurated by a speaker (natiq) prophet bringing a fresh divine message. The first six speaker-prophets, Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, Jesus, and Muhammad, were each succeeded by a legatee (wasi) or silent one (samit) who revealed the esoteric meaning hidden in their messages. Each legatee was succeeded by seven imams, the last of whom would rise in rank to become the speaker of the next cycle and bring a new scripture and law abrogating the previous one. In the era of Muhammad, Ali was the legatee and Muhammad ibn Ismail the seventh imam. Upon his return Muhammad ibn Ismail would become the seventh speaker prophet and abrogate the law of Islam. His divine message would not entail a new law, however, but consist in the full revelation of the previously hidden esoteric truths. As the eschatological Qaim and mahdi, he would rule the world and consummate it. During his absence, the teaching hierarchy was headed by twelve hujjahs residing in the twelve provinces (jaza'ir). Below them were several ranks of daees. The number and names of these ranks given in early Ismaili texts vary widely and reflect speculative concerns rather than the actual organization of the hierarchy, about which little is known for either the pre-Fatimid or Fatimid age. Before the advent of the Qaim, the teaching of the esoteric truths must be kept secret. The neophyte had to swear an oath of initiation vowing strict secrecy and to pay a fee. Initiation was clearly gradual, but there is no evidence of a number of strictly defined grades; the accounts of anti-Ismaili sources that name and describe seven or nine such grades leading to the final stage of pure atheism and libertinism deserve no credit.

Emergence of the movement. The sudden appearance of a widespread, centrally organized Ismaili movement with an elaborate doctrine after the middle of the ninth century suggests that its founder was active at that time. The Muslim anti-Ismaili polemicists of the following century name as this founder one Abd Allah ibn Maymun Al-Qaddah . They describe his father, Maymun Al-Qaddah , as a Bardesanian(Gnostic Follower) who became a follower of Abu Al-Khattab and founded an extremist sect called the Maymuniyah. According to this account, Abd Allah conspired to subvert Islam from the inside by pretending to be a Shiia working on behalf of Muhammad ibn Ismail. He founded the movement in the latter’s name with its seven grades of initiation leading to atheism and sent his daees abroad. At first he was active near Ahwaz and later moved to Basra and to Salamiyah in Syria; the later leaders of the movement and the Fatimid caliphs were his descendants. This story is obviously anachronistic in placing Abd Allah’s activity over a century later than that of his father. Moreover, Twelver Shiia sources mention Maymun Al-Qaddah and his son Abd Allah as faithful companions of Imams Muhammad Al-Baqir (d. 735?) and Jafar Al-Sadiq respectively. They do not suggest that either of them was inclined to extremism. It is thus unlikely that Abd Allah ibn Maymun played any role in the original Ismaili sect and impossible that he is the founder of the ninth-century movement. The Muslim polemicists’ story about Abd Allah ibn Maymun is, however, based on Ismaili sources. At least some early Ismaili communities believed that the leaders of the movement including the first Fatimid caliph, Al-mahdi, were not Alids but descendants of Maymun Al-Qaddah . The Fatimids tried to counter such beliefs by maintaining that their Alid ancestors had used names such as Al-Mubarak, Maymun, and Sa'id in order to hide their identity. While such a use of cover names is not implausible, it does not explain how Maymun, allegedly the cover name of Muhammad ibn Ismail, could have become identified with Maymun Al-Qaddah . It has, on the other hand, been suggested that some descendants of Abd Allah ibn Maymun may have played a leading part in the ninth-century movement. The matter evidently cannot be resolved at present. It is certain, however, that the leaders of the movement, the ancestors of the Fatimids, claimed neither descent from Muhammad ibn Ismail nor the status of imams, even among their closest daees, but described themselves as hujjahs of the absent imam Muhammad ibn Ismail.

The esoteric doctrine of the movement was of a distinctly gnostic nature. Many structural elements, themes, and concepts have parallels in various earlier gnostic systems, although no specific sources or models can be discerned. Rather, the basic system gives the impression of an entirely fresh, essentially Shiia adaptation of various widespread gnostic motives. Clearly without foundation are the assertions of the anti-Ismaili polemicists and heresiographers that the Ismailiyyah was derived from various dualist religions, such as Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism, Bardesanism, Mazdakism, and the Khurramdiniyah.

The movement was rent by a schism about 899 after Abd Allah (Ubayd Allah), the future Fatimid caliph Al-mahdi, succeeded to the leadership. Repudiating the belief in the imamate of Muhammad ibn Ismail and his return as the mahdi, Al-mahdi claimed the imamate for himself. He explained to the daees that his predecessors in the leadership had been legitimate imams but had concealed their rank and identity out of caution. They were descendants of Imam Jafar’s son Abd Allah, who had been the rightful successor to the imamate rather than Ismail; the names of Ismail and his son Muhammad had merely been used to cover up their identity as the imams.

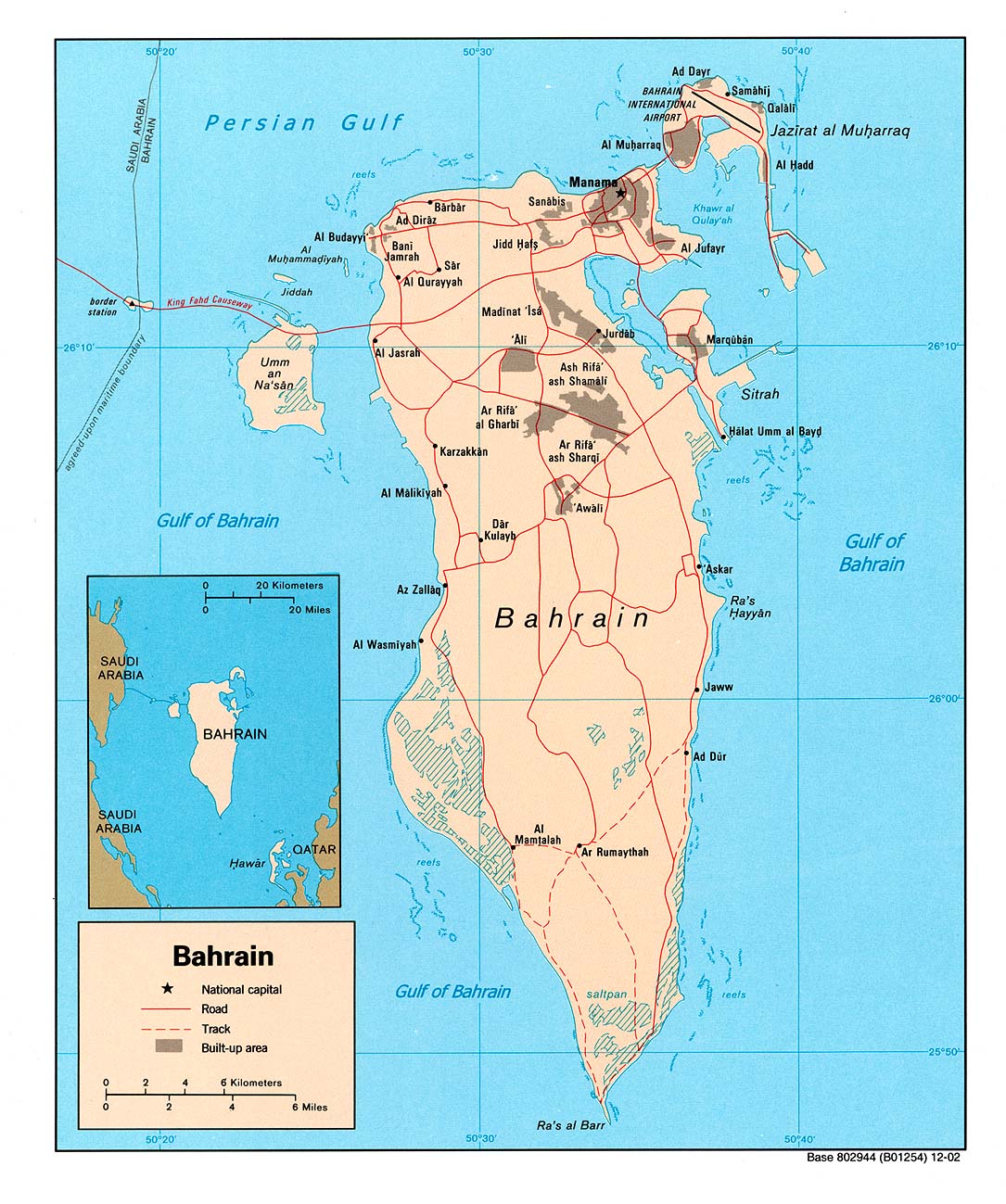

This apparently radical change of doctrine was not accepted by some of the leading daees. In the region of Kufa, hamdan Qarmat and Abdan broke with Al-mahdi and discontinued their missionary activity. Qarmat ’s followers were called the Qaramitah, and the name was often extended to other communities that broke with the Fatimid leadership, and sometimes to the Ismailiyyah in general; it will be used here for those Ismailiyyah who did not recognize the Fatimid imamate. Abdan was the first author of the movement’s books. He was murdered by a daee initially loyal to Al-mahdi, and hamdan Qarmat disappeared. On the west coast of the Arabian Gulf, the daee Abu Sa'id Al-Jannabi followed the lead of Qarmat and Abdan, who had invested him with his mission. He had already seized a number of towns, including Al-Qatif and Al-Ahsa, and had thus laid the foundation of the Qarmati state of Bahrain. Other communities that repudiated Al-mahdi’s claim to the imamate were in the region of Rayy in northwestern Iran, in Khorasan, and in Transoxiana. Most prominent among the daees who remained loyal to Al-mahdi was Ibn hawshab, known as Mansur Al-Yaman, the senior missionary in the Yemen. He had brought the region of Jabal Maswar under his control, while his younger colleague and rival, Ali ibn Al-Fadl, was active in the Bilad Yafi further southwest. The daee Abu Abd Allah Al-Shii, whom Mansur Al-Yaman had sent to the Kutamah Berber tribe in the mountains of eastern Algeria, and probably also the daee Al-Haytham, whom he had dispatched to Sind, remained loyal to Al-mahdi. Some of the Ismailiyyah in Khorasan also accepted his claim to the imamate. Residing at this time in Salamiyah, Al-mahdi then left for Egypt together with his son, the later caliph Al-Qaim, as his safety was threatened because of the disaffection of the leading Syrian daee. At first he intended to proclaim himself as the mahdi in the Yemen. Increasing doubts about the loyalty of Ali ibn Al-Fadl, who later openly defected, seem to have influenced his decision to go to the Maghreb, where Abu Abd Allah Al-Shii, having overthrown the Aghlabids and seized Tunisia, proclaimed him caliph and mahdi in 910.

THE FATIMID AGE (910–1171). With the establishment of the Fatimid counter caliphate, the Ismaili challenge to Islam reached its peak and provoked a vehement political and intellectual reaction. The Ismailiyyah came to be condemned by orthodox Muslim theologians as the enemies of Islam. The Fatimid Ismailiyyah was weakened by serious splits, first that of the Qaramitah and later those of the Druzes, the Nizariyah, and the Tayyibiyah.