justoneofmillion

Junior Member

:salam2:I thought it was important for you guys to know about him,especially due to the current events,as some are foolishly crying out basically for a duplication of the so called western model of governance,an assimilative attitude instead of one which could transform the world for the better.Why copy a declining model ,which has failed to solve the problems of the world over and over again and has brought nothing but famine,wars,enmity and despair?.Here below is a brief analysis of his magnanimous work.

Bismillah arrahmanarraheem. The attempt in this paper will be to draw the essence of Malek Bennabi’s thoughts as expressed in his book The Question of Ideas in the Muslim World and to express some of my own ideas along a similar train of thought. The book being used to represent Bennabi incorporates his most original ideas and thoughts and can itself be seen as a summary of his works. So, why is Bennabi’s work so important? As Bennabi and Mohamed El-Tahir El-Mesawi – the translator of his work – notes: this body of ideas are a framework that has the potential for a more comprehensive theological, sociological, philosophical and historical analysis. If we consider our present age to be a time when our civilization has declined and we are at a point of disintegration, such analysis becomes of vital import.

In his essence, Bennabi can be thought of as 30 years ahead of the intellectual development even in the West; the form of cross-specialization and interdisciplinary approach he has engaged in is the latest trend in the social sciences. By stating this, this writer is perhaps inadvertently pushing Bennabi into the limelight as a social scientist over and above the neat divisions of theology, philosophy, history and sociology. However, this just may be the most important aspect of his work. After all, Allama Iqbal spoke similar words from a philosophical-theological perspective. Yet, Bennabi’s connection of the dots to sociology / social human sciences is a critical and unique element, and thus it may be apt to place special regard for this salient as somehow a key genetic marker of his work.

This very connectivity to the social sciences and to knowledge itself is perhaps essential in solving a dilemma that our present intellectual environment faces. This dilemma sometimes takes the name of the “Islamization of Knowledge”, a rather Orwellian subject whose academic adherents appear stuck in a dead end. Before describing the dead end, let us define the term: they asks the question by what means today’s advances in the sciences can be sanctified and reworked to be Islam-compliant.

Now, the astute observer will note that I have already placed a judgment on this intellectual undertaking by means of framing the question. The matter is described such because there appears a lack of purpose to why we need to outwardly Islamize knowledge in this manner. What purpose is it serving and how effectively is it serving this purpose? On this particular issue, pondering over Malek Bennabi’s thoughts can help us weigh the raison de etre of this effort and in fact, understand its possible origins. This article applies Bennabi’s work to the broader issue of the Islamization of Knowledge and the specific example of Islamic Economics.

The Cosmic Void

Bennabi describes the solitude of man. He describes this as a cosmic void within man that he (Man) then attempts to fill. Two different ways to fill this void are described – either with the material or the metaphysical. Obviously, there are many other ways; for instance, filling oneself with the realm of people whose extreme can be seen in personality cults. However, all else tend to fit in between the two extremes that Bennabi mentions – the realm of objects and the realm of the spiritual.

Bennabi describes this setting beautifully with the following illustrations:

1. Man either looks at his feet or at the stars

2. Objects and forms, techniques and aesthetics, versus truth and virtue

3. Industrial time versus extemporized time[1]

4. Positivism and dialectic materialism versus morality and revealed knowledge[2]

The worldviews are also illustrated beautifully by the folk stories of two individuals in isolation – Robinson Crusoe and Hayy ibn Yaqdhan. While Robinson Crusoe fills his days with his struggle against the material world, Hayy ibn Yaqdhan is shown to spend his isolation in the contemplation of the spiritual.

Bennabi also makes the observation that for each of the two civilizations, the point of failure comes to the overindulgence of its core; for Islam it is the overindulgence of mysticism and for the West it is the overindulgence of materialism.

Commentary:

We can see in Allama Iqbal’s writings, his criticism of Ghazali as being lost in his mysticism. The popularity and acceptance of Sufism, who abandon the material world in contradiction to the example of the Prophet (peace be upon him) perhaps coincides with the slide of the Islamic civilization. Further, as Mahathir Muhamad points out, it was in the 15th century that we decided to separate worldly knowledge from religious knowledge and focus on the latter[3]. It was this that further took us away from our initial balance and inexorably into the arms of the theologians and mystics.

On the other hand, the materialism of the West has led to the increasing destruction of the moral fabric of society leading to a world were objects have overwhelmed humanity. This world is the anti-thesis of the push to mysticism. Perhaps one pole attracts the other.

The question that comes to mind is, given the completely different core viewpoints of the two worlds, can we attempt to Islamize Western knowledge in the manner we are attempting at present? The dominance of Economic theory in the West aligns with the dominance of the material. For instance, the very term “Econom(y)ics” resides in the material. Simply attaching “Islamic” to form a “new” “Islamic Economics” seems dishonest to our true principles, to our very different core. It seems that the very aspect of Islamizing knowledge today does not reach out and spring forth from our core, but attempts to fit our principles into a Western creation.

A respected author at an Islamic university wrote a book using such complex terms that the students (at least those for whom reading it is compulsory) are dumbfounded at what it means. Looking at the same book, this author admits he has never heard the term “prolegomena” before. These wonderfully complex terms are then put together in such a vague manner that you are left wondering what the author is saying, but give the benefit of the doubt that it must be truly profound. On the other hand, perhaps Bennabi’s words were apt for this:

Islamic thought sinks to mysticism, to vagueness and fuzziness, into imprecision and into mimesis and craze vis-à-vis the Western “thing”!

We must ask ourselves what we are trying to achieve, or who we are trying to impress with this approach to writing. And in the sixth chapter of the book, Bennabi describes the issue of a lack of ideas or dead ideas leaving empty brains, helpless tongues and infantilism. He quotes Nicholas Boileau a French literary critic from the 17th century thus:

That which is properly thought out is said clearly,

And the words to express it come forth easily.

From the above perspective, taking the concept of Islamization of knowledge as illustrated by “Islamic Economics”, the very idea is perhaps fundamentally flawed in creating an Islamic revival. The learned scholars react by stating that we cannot go back and start from scratch. But such scholars miss the point that there is a big area between the dressing up of Western sciences to meet the Islamic hijab code on the one hand, and “starting from scratch” on the other.

In the West, Economics has triumphed in taking the crown of the social sciences, perhaps because of the importance of the material origins of the Western zeitgeist. But in solving the problems of an Islamic society, it may be more relevant to look at society from a more holistic perspective, perhaps in a new categorization of “Islamic Socionomics” or “Maslahanomics” that is more multidisciplinary than the paradigm of Economics allows. Shatibi framed his maslahah with a similar holistic approach. There is no reason why we have to be presented with an either-or choice between rejecting Western social sciences and starting from scratch, on the one hand, or taking their baggage either wholesale or with the addition of a superficial compliance.

Yet the latter is all that we have achieved in producing; meaningless re-workings of Neo-classical and Keynesian models and replacement of interest rates with “profit rates” and the addition of zakat into the models.

But, what is the nature of knowledge and why is it important to us? Even before we can touch upon the question of Islamic Economics and Islamizing knowledge, we have to first identify the nature of the relationship between Islam, Muslims and knowledge. It seems that we understand knowledge in a vacuum. As if it was something necessary for the survival of the material world. Our universities churn out degree holders to feed our economies in the hope of competing with the West. We then Islamize our text to make them more palatable and to claim an Islamic revival. Yet, this reaches out to a mimic of the West seeking its core in the material. Our focus on the reason, purpose and relationship of knowledge to us has to be fundamentally different. It has to reach out to our core – our religious and spiritual innards.

There may be many different means by which we can develop this connection. It is up to our intellectual endeavour to take up this challenge. The connection is expressed in the following section based on this author’s understanding. It is noted that this is but merely one way to think about the issue.

Islam and the Knowledge of the Sciences

The story begins (and Allah knows best) when Adam was created and Allah (swt) taught him the “names of things” or “nature of things”. And Adam was asked to tell the angels their “names” or “natures”. And this was seen as the triumph of man and convinced all but Satan. All were told to bow to man – what an ultimate honour to be bowed to by Allah’s creation!

At first glance it seems confusing. What is this term “names of things” or “nature of things” and why was it so special? For many people this would just be something they will not understand or contemplate over. Was it that the angels did not understand and simply start bowing to anyone that can take their name or show their nature? Moreover, what is the point being made by the Quran? Is there a point? Perhaps the Quran isn’t stating a senseless idea. Perhaps there is some real meaning in this.

Perhaps for a student of psychology this could provide an interesting paradigm. Consider the fact that studies of the human mind have shown that the mind has an amazing ability that other beings known to man do not have – the ability to classify things – both material and non-material (i.e. ideas). This ability to classify information is not shared with other creatures. If you read about the philosophy and epistemology of science, you find that this quality of classifying data and thereby investigating their natures is perhaps the key factor to what science essentially is. In fact, it is what science is built upon, it’s very fundamental building structure.

The reason a university has so many departments each focusing on a specific set of subjects, and within them sections focused on even more specific, and within them sub-sections and professors who specialize in even smaller focuses is because the information has been classified into these various branches, sub-branches, sub-sub-branches and so forth. This makes the investigation of the nature of things possible at a level unforeseen otherwise. So, what this author is crawling towards is that the event when Adam was created and thereafter was taught the names of things, was not a meaningless event, but a very meaningful one and one that guides us as human beings to who we are, what we are, and our purpose.

To clarify, our purpose is to worship Allah (swt) as we all know. But does worship mean going to the masjid and banging our head to the floor a couple of times while thinking about our daily activities and then being on our way? As always, when in doubt, investigate the Quran. The Quran constantly, and repeatedly talks about reflecting, thinking, contemplating about the world Allah (swt) has created around us. One random example of many:

And all things We have created by pairs, that haply ye may reflect. (51:49, Al-Quran, Pickthall)

The second thing you notice is that the Quran talks about the natural world (botany, zoology, evolution, etc), about the stars, planets, the beginning of the universe (Astronomy, Astrophysics), the mountains (Geology and Geography), and more. Again, it simultaneously (and repeatedly) tells us to think, reflect, and contemplate. Islam goes so far as to challenge man to find a fault or prove the Quran wrong.

Allah knows best, but the purpose of this can perhaps be best understood in the following manner:

Imagine that I make an acquaintance. I can say hello, ask his name and meet the individual repeatedly. But after a million hellos, I may not truly know him any better than the first day I met him. If I really want to know the individual in question, I could perhaps take another approach. If the acquaintance was a painter, I could go down to look at his painting and attempt to understand him through his works. My mind may wonder: what does my friend paint about? Women, cars, landscapes or science fiction? What choice of colours does he use? Is he a cubist? What size are his paintings? What’s so great about his work? What’s not that great?

On the other hand, if the acquaintance was an engineer and had built a bridge, I could go down take a look at the bridge, see what it’s like – is it mechanically efficient? Aesthetic? Both? Is it sporting a postmodern looking? Or does it look like it’s out of the 18th century? What choice of materials did my friend use? By noting the works of my acquaintance, I could get to know about him in a more meaningful way than having spent years saying hello and goodbye. Perhaps even more than if I chatted with him about the weather, the news, politics, religion, philosophy and had tea with him every weekend.

In a similar vein, if we wish to know our Creator, one critical method could be to contemplate, reflect, and think about His amazing creation (and Allah knows best). But to effectively do so, we need to understand the nature of the things around us. We need to have some idea of art to understand a painter and some idea of the engineering of bridges to appreciate our engineer friend who built one.

This brings us back to the parable of Adam. To really understand the nature (or names) of things, we need to be able to classify them and study them in depth; to be investigators, scientists, thinkers, theorists. We note that only humans have this ability to classify data, that is to name them, and this is closely connected to understanding their natures. Because once you can classify data, you can begin to investigate the relationships between multiple classifications. This mental process may seem natural to us, but in fact is unique to humanity.

So a Muslim, who actually reads the Quran with understanding and contemplation, not mindless babbling while rocking left, right, forward and backwards, will inevitably become an investigator, a researcher, a thinker, a philosopher, a scientist. What is more, this is closely linked with tauheed and tasawuf.

Tauheed is often described as the understanding of the Oneness of Allah and knowing his attributes. Only by being an investigator, scientist, thinker, can we get a deeper understanding of the Oneness of Allah, which is constantly expressed in the creation. Otherwise, repeating the Names of Allah will neither yield a deeper understanding of those Names nor will it be sufficient in itself to attempt to understand our Creator with the full force of the resources and capabilities available at our disposal. Thus, our scientific endeavour is central to the goal of reaching a more meaningful and deeper understanding of tauheed.

However, charting the destination is different from walking the destination. When we begin our investigations, we quickly find that our mind gets involved with the specific and forgets the whole. If we take the bridge example, you start admiring the bridge, the materials, and the architecture and forget about the engineer who we hoped to better appreciate. This is where the role of tasawuf begins; the constant remembrance of Allah; in our case, specifically during our investigation. Without this, we lose the purpose of our investigations and are lost again into the world of objects and people.

Thus, tauheed, investigation of the sciences and tasawuf / dhikr are inextricably linked. None can exist in their essence in isolation but are joined like a jugular vein to the other. In the great contemporary battle between the Wahabis who nominally uphold tauheed and Sufis who nominally uphold tasawuf (or dhikr), both sides have missed the essential symbiosis of the three concepts. If anything, all sides consider the investigation of “secular” knowledge as beyond their realms and subject matter.

The Embryology of Ideas

Bennabi describes the development of a child as he moves from recognizing objects to people and finally, to understanding ideas between seven and eight years of age. He notes that the effect of ideas on a child is powerful and far-reaching and points to how it even affects an individual’s physiology:

A half-open mouth, ready to grab and suck anything, is a salient feature of the small child. However, as he grows older, his mouth closes as if driven by some internal springs. This morphological detail actually corresponds to a specific phase in the child's psychological development.

He notes that these physiological differences are also observed between those who are educated and the illiterate[4]. Bennabi notes that the three realms of objects, people and ideas hold different levels of strength over an individual depending on the individual and the society he lives in. If the society is object and people focused, the aggregate of individuals that it reproduces will share that balance. Bennabi points to the object and people focus of Muslim society today as the symptom of our decadence.

Commentary:

Our present education system, whether madrasah oriented or secular, or in the case of an Islamic university an attempt at something in-between must be recognized as part of the problem of why our children are being inhibited from growing into the world of ideas and thought. After all, entering the world of ideas is the natural culmination of the psychological and biological processes, particularly with a Quran already in hand. We must ask ourselves, what is it that we as Muslims do to our children that we rob them of the ability to grow into their full potential, only achievable by reaching the full growth into the world of ideas?

It may be that we are forcing our children into boxes out of which they cannot grow out of. Like in China where it was once believed that women having small feet are highly desirable. As a result, they began to put their children into shoes from which they could not grow out of. Our situation may be worse for we cannot observe by sight the damage that we are doing to our children.

While teaching some fellow classmates and friends Malek Bennabi’s book, I came across an interesting symptom. Friends and classmates could not understand the book by reading it. Their argument was that the language was too difficult for them to understand. However, when I opened the book and told them to point out what words they didn’t understand, it quickly transpired that it was beyond just difficult words. It seemed to me that it was hard for them to grasp the large number of sophisticated ideas that the book was throwing at them.

Yet another incident reflected upon this phenomenon, a brother, while discussing thoughts and ideas with me asked me how I deal with thinking about all the things that I think about. He describes that if he thinks too much, it hurts his head.

These incidents and Malek Bennabi’s diagnosis bring us to an important question: why is it that our children can regurgitate vast amounts of information, both “religious” and “secular”, yet have an inhibition in terms of being able to think? Is it something we are doing to them that is causing this pathology?

Civilization & Society

Bennabi discusses three stages of a society:

1. Pre-civilized society

2. Civilized society

3. Post-civilized society

He describes the post-civilized society as one that has reversed the direction of its movement and is now moving backwards. Bennabi considers the Islamic civilization to be a post-civilized society that is now regressing back to a world of objects and persons.

Bennabi describes how Islam started in Jahili society were people lived in the world of objects and people. Islam broke this mould and brought the society into civilization and the world of ideas within three decades.

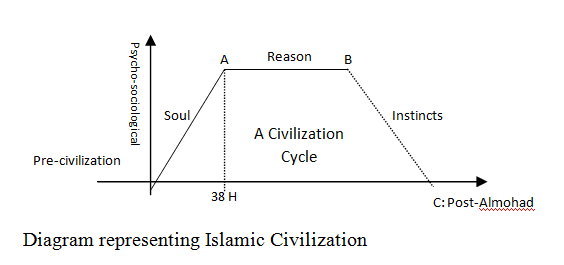

He defines civilization as “the sum-total of the moral and material conditions enabling a given society to provide each of its members with all social guarantees necessary for his development”. He points to the vital importance of society and civilization to man: without it, man can barely survive. He states that the will and power of society gives civilization its objective character. Society’s will and power differs depending on what phase society is in. He illustrates these stages by using a diagram similar to the one below:

Bennabi visualizes the stages of the Islamic civilization with the diagram. To him, it represents the psycho-temporal values of civilization. Our civilization began at the origin point in Ghar-e-Hira. Here was born our purpose, will and morality. Until 38 Hijri, we had a rapid rise as we remained faithful to our spirit, values and methods. In 38 Hijri, after the Treaty of Siffin and the division of our state, we lost our “soul”. Thereafter, we continued in a plateau trajectory which Bennabi describes as “reason” with many scientific developments and a continuation of the intellect. Between point B-C we began to move away from Reason and move increasingly towards taqlid on the one hand and mysticism on the other. Bennabi marks the decline of the Muslim civilization with the fall of Grenada in the West and the fall of Baghdad to the Mongols in the East.

Bennabi describes the first spiritual phase as one where the newly formed society deals with its problems by suppressing needs and maximizing utilization and distribution of resources at hand. He describes this stage as the most beautiful forms of asceticism exemplified by the Prophet (peace be upon him) and the generosity of the Sahabah in giving their wealth to the greater cause.

As the resources of the society expand in conjunction with the spiritual and intellectual endeavour, the power of the society also expands, marking the dramatic rise of the initial state in Medina. Bennabi notes that the power of the will is kept intact because of the strength and vitality of the ideas that creates a tension within every Muslim. He notes that this is a distinguishing characteristic of the origin-to-A phase. In the A-B phase, gradually the object takes increasing prominence until it takes hold, particularly in the B-C phase.

Commentary:

It is obvious to us that we are well past the B-C phase and have lost Islam and are wallowing in the pits of objects and people. This world of materialism on the one hand and mystical rejection of the world on the other has polarized the Muslim masses and robbed them of the Islam in the middle. Perhaps the former began with Muawiyyah and Yazid, while the latter imprinted itself on the early Sufis.

This brings into play a new form of self-sustaining tension, one where the materialism push the mystics into greater mysticism and rejection of the world, while the greater mysticism and rejection in turn, push the materialists to greater materialism in rejection of the mystics. This cycle plays out over and over, with each cycle further polarizing society. Muslim society is thus split. Each of these poles begins to see itself as distinct and find names to define themselves. Thereafter, they become institutionalized and a profession and doctrine are built. Thus, the foundations of a secular society get built, long before secularism becomes an explicit force.

Imam Ghazali left Baghdad in the rejection of the material, and as Allama Iqbal states, eventually became lost in his mysticism. Yet, many authoritative sources claim him to be beyond rapprochement, beyond criticism and his works are used as the basis of the doctrine expounded by the ulema for a number of key regressive elements. One of many of these includes a supposed closing of the doors of ijtehad.

On the other hand, Ibn Taymiyyah began as a Sufi and then moved to rejecting mysticism, yet went in another direction. His thoughts and ideas have been interpreted to reflect a literalist approach, an approach that is better familiar to the world of objects and people. This can perhaps be described as the objectification of ideas. While he realized we have lost our origin, his approach could never have succeeded, for it had lost the world of ideas and was stuck in the world of mimesis. Thus does he (Ibn Taymiyyah) call for us to go back to the Sahaba, rather than the original principles and their methodology of expression given by the Quran and the life of the Prophet (peace be upon him), respectively.

It is telling that Muslim society today are so sensitive about both these individuals, such that they place them in an era they call the “Golden Age” and strongly react to any criticism of them. In fact, they allow such criticism itself only to traditional “scholars” who themselves are the heirs to the institutional and doctrinal poles. While the traditional Muslim clergy are living in this world of persons, the Wahabis are wallowing in a further step backwards, in the world of objectification of ideas as described earlier.

This vicious cycle of the polarization of the Ummah was further accelerated by the entry of the European colonists, who found our Ummah fertile land to plant their seeds in support of the materialists. After all, an artificially anti-materialist mysticism brings about a vengeance of betrayed ideas[5]. This is sometimes seen clearly in the historical account. The Indian Subcontinent was colonized by the British through their foothold in the province of Bengal. Here the battle was lost because a body of Muslims were bought off and betrayed their side for the material benefit to themselves. Another example is of the Wahabis who, while willing to blow up anything and everything they consider bida, have been long-time allies of the West who have indulged them well in their materialist excesses.

Malek Bennabi describes the problem of being colonized as not only one emanating from outside our civilization, but also from within; that we are only colonized because of our colonizability. We attract the mice with our lack of housekeeping.

The Contextual Power of Ideas

Bennabi writes that the conditioning power of ideas, the ability to effect changes in society, is not the same for different civilizations. He illustrates how the ability to effect change in the material world is harder for the West because of their cultural roots. He gives the example of the Prohibition in the United States and its ineffectiveness while for Muslims, it was a simple matter of the Prophet (peace be upon him) prohibiting alcohol, the drinking of which vanished overnight without any needs for extensive policing.

Bennabi believes that this conditioning power varies within the Muslim civilization’s passage through history, in the different stages that he described earlier with his diagram.

Bennabi describes the power of ideas as dependent on how effective the impressed (or original, universal principles) are in their transformation to the expressed ideas (or derived ideas). In their original use, the impressed ideas are in their peak of potency. However, as time changes and the world around us changes, the ideas become less effective in their application. An attempt to create an effective new interpretation of the original ideas can often lead to the expressed ideas becoming betrayals of the original ideas. Bennabi explains that this betrayal can lead to vengeance from the original idea. He gives the example that an ill-constructed bridge will collapse and the tragedy that follows would translate to the vengeance of the betrayed ideas.

Bennabi explains that society, civilization and empires fall in the same way. He explains that dead ideas leave a void in the brain which in turn causes an inability for society (and individuals) to express themselves effectively as we saw earlier with the Islamic scholar’s peculiar use of words. Closer to the end of the book, he describes dead ideas as attracting deadly ideas[6]. He considers the state of dead ideas as causing the basis for colonization and expresses this state as colonizability.

Bennabi identifies three levels regarding the parameter of actions where ideas can be betrayed:

1- The political, ideological and ethical level concerning the realm of persons. (Perhaps also the psychological level).

2- The logical, philosophical and scientific level concerning the world of ideas.

3- The sociological, economic and technical level concerning the world of objects.

Bennabi describes the distortion of original ideas, on these three levels, over time and space. He compares the original message of Islam, to the distorted message today with a description of Jeddah airport, “Office of Enjoining Good” and the actual practice of the people observed there. He points to dead and betrayed ideas being supplanted with ideas from a foreign civilization, which end up being deadly to the host civilization.

Commentary:

In the case of Islamic Economics today, the question we need to ask is, whether our expressed ideas[7] are honest to our impressed ideas[8]. Is the very basis of Economic theory honest to our impressed ideas? These are questions that our Economics scholars need to ponder over. Perhaps they fear to know the honest answer to them, for that would put them into a quandary of having to rework their profession. Perhaps they fear how acceptable this will be to the international intellectual community. But perhaps these are but problems that are the consequences of issues with all three parameters of action categorized by Bennabi.

Perhaps the Muslim world is like a hut with pillars that have all given way. Now, if we attempt to prop up one support, the hut will not stand, for the moment we go to the next pillar, the roof has collapsed again. For the single pillar cannot support the roof.

Regarding Bennabi’s three parameters, this also provides an interesting paradigm from an epistemological viewpoint for the development and categorization of a basic superstructure concerning an Islamic general theory of thought.

Dialectics

Bennabi states that the Muslim world, while recognizing its decline, has two archetypical responses as to the cause of this decline. He describes one side as the supporters of the colonialist thesis who blame Islam and the other side he defines as the nationalist thesis that blames colonialism. He notes that the supporters of colonialists disregard the role of Islam as one of the most magnificent civilizations of mankind. On the other hand, the opposing side ignore that the most backward countries have not experienced the colonial challenge, such as Yemen.

To Bennabi, neither side has the solution and are part of the problem. He notes that any solution must begin with beginning from an unprejudiced mind (unprejudiced by either group). He finds that we are stuck in the world of objects, peoples and the betrayal of impressed ideas. He blames our inability to adapt our impressed (or original) ideas effectively on the one hand, and our lack of faith in our ideas when we transplant them with ideas from foreign civilizations.

Ignorance as Paganism

Bennabi argues that if paganism is ignorance, ignorance is necessarily paganism. The ideas of Islam defeated the objectification of the idols of jahaliyah. He gives the example of how zawiya, veneration of saints and seeking of spiritual blessings through talismans, prayers at shrines, etc, is in fact a return to our age of jahaliyah. He notes that when the idea disappears, the idols reappear. He describes the role that the “ulema” have played in Algeria to push Islam backwards to the world of ignorance and idol-worship. Bennabi marks an important turning point in the move from ideas to idols when Islam moved from ijtehad to taqlid. He gives the example of how al-‘Izz b. ‘Abd al-Sallam blamed the jurists of his time for taqlid.[9] Yet today, taqlid is untouchable.

Commentary:

This latter issue is a much visited issue by Tariq Ramadan who emphasizes the maqasid over the application of the shariah from a juristic perspective.[10]

Genuineness & Efficiency of Ideas

Bennabi makes the point that Europe has given primacy to efficiency in its colonial order. This has caused the secular elites in the Muslim world, who are impressed by the Europeans, to focus exclusively on the efficiency of ideas. He notes that Europe’s other face is one of an inward ego and a peculiar ethical order. This is not visible to the secular elites who are impressed by the efficiency of her ideas and adopts wholesale all ideas in the belief of their effectiveness. Because they can only view this one side, they are unaware that ideas have another key aspect: their truthfulness or genuineness.

Ideas and social dynamics

Bennabi views the world of ideas as not merely an intellectual endeavour that does not impact the world, but rather one which is centrally important to reviving society. He states that the purpose of planning is to revive social dynamics and the methodology and formation of the plan must be honest to the intrinsic ideas of the civilization. He notes that this planning can only be effected from a wider viewpoint than Economics can provide; for the economist inevitably denigrates the non-economic aspects and does not have a holistic view of society. Bennabi notes that sociologists are more suitable for this role.

He notes that our plans cannot be a mixture of planning methodologies because “any project conceived according to the ideas of one doctrine and implemented according to the means of another will lead nowhere”. Thus we cannot accept a mixture of capitalist and socialist theories. We have to look at the problem and build on our own methodology that is honest to our intrinsic principles if we are to have the desired effect on our society’s problems.

Commentary:

This author’s view however, is that sociologist in turn subordinate the economic and may not appreciate the effectiveness and importance of economic theory. It is thus advocated there be a creation of a new Islamic methodology and epistemology that combines the social sciences more effectively; perhaps as earlier mentioned a science of “Islamic Socionomics” or “Maslahanomics”.

Beyond Revolutions

Bennabi notes that revolution takes place at the point of utter exhaustion of a society. He however notes that revolution by itself cannot solve the problem. He notes that revolutions can end up taking the society back to the pre-revolutionary stage or worse. Bennabi writes about the Marxist dialectic and its importance in studying revolutions. He finds that the Marxist dialectic cannot solve the revolutionary issues in the colonized and ex-colonised countries.

This is because Marx’s dialectic method is used to analyze countries that have a single cultural universe while the ex-colonized countries have to share the ideology of not only the host cultural universe but also the alien cultural universe.

Bennabi also notes that Marxist thought could rely on ideas alone as a force of change, given that they were propounded in a society which had entered the world of civilization (a world of ideas). However, the Muslim world is living in the world of objects and persons, thus they need the ideas to be validated by objects or persons before they can be a force in society.

Bennabi explains some key salient for enlightened politics. This includes the need for faith in the ruler. He considers morality as an important characteristic in the ruler but not the only characteristic but must include competence and compatibility. He commends the model of Medinah at the time of Umar as a model which our political systems should strive towards. He considers politics to be a science, an applied sociology.

If we pursue our idea of “Islamic Socionomics” or “Maslahanomics” and follow a methodology based on classifying certain knowledge as downstream like politics, we could perhaps build a new structure of knowledge. One possible example is given below:

Here we have the upstream Maslahanomics and downstream applied Socionomics in Finance, Politics and Military Science.[11]

Conclusion

Bennabi notes that the Muslim world today is at a risk of being overwhelmed by the West, at the very moment that the West is in decline. He notes that if it seeks to follow in the footsteps of Europe, it will always lag behind the West as it has to go through the same steps that the West has already long passed. He notes that we cannot make history by following beaten tracks; it is only possible to do so by opening new paths. Bennabi explains that making history will only be possible for us if we return to our genuine principles and derive from them efficient solutions for today. This requires us first to get out of our Jahiliyah and back to the world of ideas. Thus, the question of ideas remains one of the paramount questions in the Muslim world.

[1] Bennabi calls this the detemporalization of time, where the Islamic world undervalues “time” and focuses instead on a “time” based on spiritual events. This writer would note that practicing Muslims are most driven by “time” measured by the yardstick of the five daily prayers, the sacred months, the major religious holidays and so forth.

[2] Bennabi actually describes it using the phrase “the love of good and the aversion for evil”.

[3] See “Islam and Science” on Mahathir Mohamad’s website: http://chedet.co.cc/chedetblog/2010/02/science-and-islam.html

[4] This author sadly notes that many Muslims today, although nominally readers of the Quran, continue to exhibit the characteristics of the latter.

[5] Bennabi describes betrayed ideas as ideas that have lost their original genuineness emanating from their origin. Islam originally sought to subordinate the material world, not reject.

[6] Deadly ideas: ideas foreign to the host civilization that are harmful for the host because of their alien origins, just as in the case of an introduction of a creature into an ecology from outside can cause havoc in the host ecology.

[7] Expressed ideas: ideas that are derived from our original principles (impressed ideas) and that target the world around us with the aim of being effective and at the same time being true to the original ideas.

[8] Impressed ideas: Original, genuine, timeless ideas that derive from our core belief systems.

[9] Al ‘Izz ibn ‘Abd al-Salam (660 Hijri / 1240 AD) lived in Syria and Egypt and was a scholar and jurist. He is known for his position against taqlid and is principled political stand. His work Qawaid al-Ahkam fi Masalih al-Anam (Principles of the Shariah Commands Concerning Man’s Good) is an important work regarding maqasid.

[10] See his speech titled “Islamic Renaissance: The Need for Renewal & Reform” delivered in Kuala Lumpur in 2010.

[11] While it is unconventional to include Military Science here, this author notes that the allocation of resources is also a critical element in Military Science.

http://www.grandestrategy.com/2011/02/thoughts-on-malek-bennabi-have-muslims.html